Race, religion, politics, faith

How cultural Christians misunderstand the wider world.

There’s only one religion in the world. There’s also a dīn and a dharma and various other expressions of the supernatural, but the only one that fits neatly inside the definition of ‘religion’ is Christianity.

That’s because Christianity was shaped by Latin Europe, which also gave us the word religio. Other belief systems are different in concept and in scope; the boundaries implied by the Christian understanding of the word ‘religion’ don’t necessarily apply.

In multicultural Europe, we need to understand these nuances. As societies polarise, previously academic questions about religious identity – is Islam compatible with personal freedom, can Judaism be separated from Zionism – have become acutely political. They can only be answered by looking beyond the cultural framework of Christianity.

Religio and Christianity spread through Europe in tandem. When countries adopted Christianity they also adopted the Latin word to describe it: Nearly all European languages, from Russian to Polish to Irish and even Basque, now use a derivative of religio instead of a word with a local root.1

Consider the Vikings, who evidently saw Christianity as sufficiently distinct from the Norse pantheon to require a new word to describe its place in public life. Ásatrú, meaning ‘faith in the gods’, made way for the Old Swedish religion, whose Latin etymology carries ideas of ‘obligation’ or ‘bond’.

But since then, we have begun to use the word ‘religion’ in a more categorical way, referring to other faiths as well. Language is destiny: Politics is downstream of culture, and culture is downstream of language. The linguistic elision of ‘religions’ has made us suppose, at a subconscious level, that they’re all broadly Christianity-shaped.

They’re not. Each supernatural belief system occupies a distinct range of brain-space and touches on different areas of life, with important effects on how it interacts with politics and society.

Render unto Caesar

Consider the limits of Christianity and how they inform European political thinking. Christianity makes no claim to ethnicity or nationality: As a proselytising religion, it aims explicitly to straddle such borders. As such, in the European mind, religion is clearly distinct from questions of race or nationalism.

But not every belief has that separation. Judaism is an ethnicity as well as a spiritual belief. Jews have never dispatched missionaries; on the contrary, access to conversion is closely guarded. Almost every Jew alive today is therefore directly descended from the ancient Israelites, and that fact is a central part of Jewish identity and religious practice. It’s also at the heart of Zionism.

Christianity makes space for temporal authority, most obviously in the phrase attributed to Jesus: “Render unto Caesar that which is Caesar’s, and render unto God that which is God’s.” Christian texts overlap with family law and medical ethics, but not with taxation or foreign policy. As such, Europeans instinctively perceive a fairly clean break between politics and religion.

That marks a contrast with Islam, which dictates a much broader range of public affairs. The Quran explicitly states that the global community of Muslims (the umma) should be governed by a single state or federation with God as its sovereign and run in His name by a caliph – a ‘successor’ to Muhammad. It provides detailed instructions on matters as diverse as taxation and slavery. It claims jurisdiction over the whole world, and refers to places not yet under Islamic rule as the dār al-harb – the House of War.

In reality, most Muslims in Europe are able to set aside these commandments and practice their religion in a more limited fashion. But because Islam is so comprehensive in its concept, the gap between religious theory and lived reality is arguably wider for Muslims than it is for any other religious minority.

Beyond the Abrahamic religions, things get even less familiar to those of us raised in a Christian framework. Hinduism, Shinto and so forth are vastly different from Christianity – and from each other – in which questions they address, as well as how they address them.

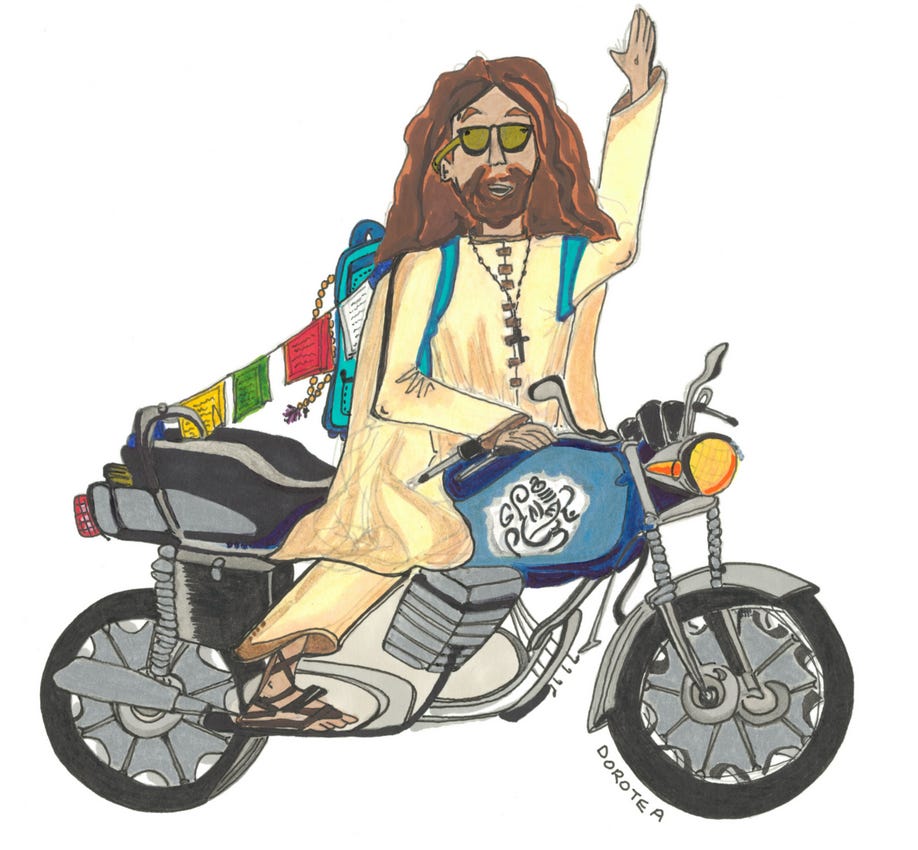

Some years ago I spent two months motorcycling around India.2 I rented the motorbike from a Sikh gentleman, who gave it a blessing under the auspices of Ganesh, the Hindu god of travel and other things. A week later, as I entered the Himalayas, I was given some Buddhist prayer flags to drape around the handlebars.

None of these things were seen as conflicting with each other or with my Christian-infused atheism. Indian faiths are syncretic, their gods less jealous than ours. For my part, I happily went along with it. On Indian mountain roads, the wise man takes all the heavenly help he can get.

Our kind of heretic

I have been an atheist since I was a child. I don’t remember exactly when I stopped believing in God but I do recall that it was only a year or so after I gave up on Santa, who Himself only lasted a year longer than the Tooth Fairy. To my young mind, these three supernatural entities were on a continuum.3

In the last months, though, I’ve started thinking of myself as a Christian not because of any belief in God but because of how I conceptualise religion. My instinctive view of where the boundaries lie between race, religion, politics and faith is typical for someone raised in the Christian tradition.

The historian Tom Holland has even argued that atheism itself is a Protestant concept, since the idea of religion being a personal matter, held separate from communal belonging, was only introduced to Europe after the Reformation.

My sense that religion is optional was so entrenched in my formative years that I remember being shocked, even feeling disrespected, when a Christian identity was first forced upon me. In my early 20s I began travelling to the Middle East and was required to declare a religion for my various visa applications. These typically had a drop-down menu with no option for ‘atheist’ or ‘none’, requiring me to declare myself Christian.

Over the subsequent months I spent travelling in the Arab world, I discovered that the vocabulary for my spiritual worldview doesn’t exist. There is no word in Arabic for ‘atheist’. The closest I could find was mulhid, which more accurately translates as ‘heretic’.

The only way I found in Arabic to describe my lack of faith was lā mutadayyin, literally ‘not devout’. It’s a negatory expression, not an affirmative one, suggesting a lack of character rather than a considered viewpoint. Here, too, language is destiny.4

Since heresy isn’t conducive to making friends and influencing people, I gritted my teeth and said I was a Christian. At the time I thought it was a lie, since I have no faith in any god. Now I consider it to be true on a deeper level: My ability to dispense entirely with faith reflects the Christian nature of my cultural upbringing.

These nuances are important to understand but also difficult to discuss. Ironically it’s our own concept of religio that makes the topic so sensitive. For European Christians, public politics is open to criticism but personal faith is not. In other traditions, the two can’t be so cleanly separated.

The major exceptions are Greek, which has its own complex relationship with Christianity; and Hungarian and Finnish, which God created to frustrate linguists.

A more commercially-minded boy might have feigned continued belief in the Tooth Fairy and Santa for the obvious material gains he could extract; I understand many American businessmen attend church for the same reason.

Arabic also uses the same word for ‘clergy’ as for ‘scientists’: ‘ulema, literally ‘learned men’. This gives religious teachings an aura of empirical truth that is reflected in the region’s politics.

I had the exact same thoughts, which you expressed very well !

Another good example is the status of buddhist monks in Theravada buddhist countries (Thailand, Myanmar, ...) Monks have specific laws that only applies to them. If a buddhist monk breaks celibacy, it's not just spiritual matter, he will also face fines or jail time. And there's more; they cannot vote, cannot inherit, and they cannot make financial transactions. But on the other hand they cannot be jailed, insulted or drafted in the military (higher rank only).

And in Theravada buddhism, being a monk is not just supposed to be reserved for 'the clergy', it is a necessary step to enlightenment, meaning any Theravada buddhist is supposed to become a monk at some point in his reincarnation cycle.

This shows quite well the limits of our western concept of freedom of religion; We clearly cannot allow such monks to have such different legal status as this would put one religion apart from the others, and open the door to all kind of crazy laws. But you can argue that you cannot really practice that religion without the special legal status granted to monks either.

I think this is also a better example to argue about this than judaism and islam since it's much less politically loaded.