Reverse Paris Syndrome

Japanese cities are better than ours.

When a Japanese tourist visits Paris, they may experience disappointment intense enough to cause trauma. Paris Syndrome has been a recognised condition since the 1980s, long before it and other European cities became known as crime hotspots.

As a child of the European metropolis, I used to find such squeamishness amusing. But now I must say sumimasen to the Japanese people because after visiting their wonderful country, I have begun to understand how jarring it must be for them to visit Europe.

This is not simply a matter of difference. I am probably less familiar with the food and language here than the average Japanese person is in Paris, but I don’t have anything resembling Paris Syndrome. What I’m feeling is closer to the opposite.

Reverse Paris Syndrome is the jarring realisation that so much of the shit we put up with in European cities is unnecessary, and the platitudes we tell ourselves in order to cope are untrue.

All across Europe, we have learned to accept high levels of crime as a cost of living in the city. We’re constantly looking over our shoulders, patting down our pockets, avoiding certain areas at night. When something is stolen regardless, we thank the fates that we weren’t stabbed as well.

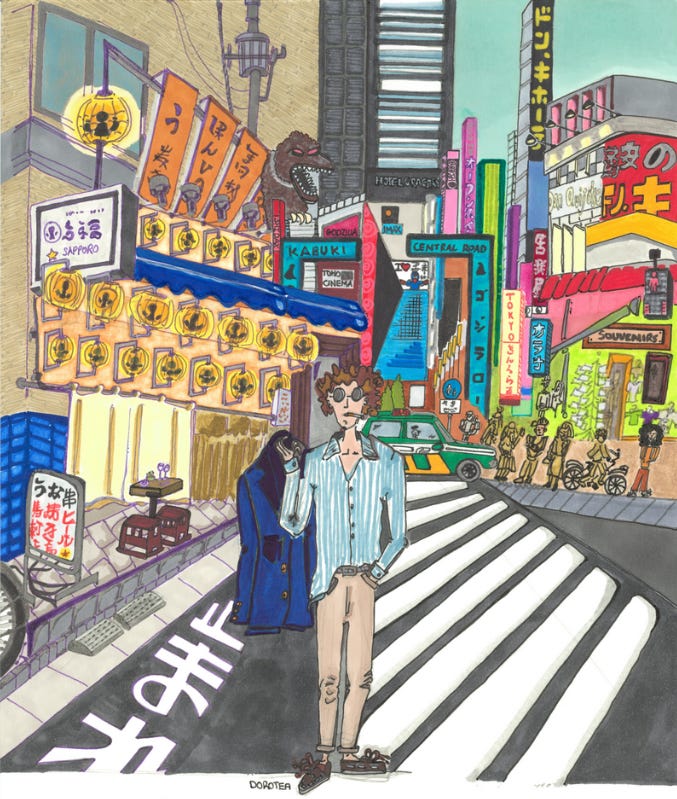

In London, thieves on e-bikes seize watches and smartphones with impunity; the authorities meekly tell us to be more vigilant. In Tokyo, you can leave your phone on a restaurant table while you go to the bathroom. London has legalised bike theft; in Tokyo, people leave their bicycles unlocked overnight outside their houses. Visitors can make use of luggage lockers, which somehow survive the night without being pissed on or broken into.

After a couple of days in this environment, I started putting down a guard I had forgotten was up. I’d ride the metro without moving my phone and wallet from my loose jacket pockets to my trousers. I’d leave a laptop unattended to talk to someone. On the shinkansen to Hiroshima, I napped through a few stops without waking up each time to watch my bag. It was a revelation.

Excuses melt away. Tokyo is not a tightly controlled city-state like Dubai, where the poor are housed in distant compounds and criminals can be deported at will. It is a thriving, humming metropolis, by some measures the biggest in the world, and low-level crime is simply absent. So is antisocial behaviour. There’s no litter or graffiti; everyone wears headphones when listening to music.

More than a monoculture

It would be easy here to attribute the difference to Europe’s cultural diversity, which is so obviously lacking in Japan. There’s a trope in right-wing politics that Western cities could all be like Tokyo if we abandoned multiculturalism, stopped pandering to ‘communities’ and reinforced a broader sense of society, restoring social trust. There’s a grain of truth to it.

Japan is tentatively beginning to bolster its workforce with foreigners, and many Japanese see multicultural Europe as a cautionary tale. Stories of Muslim migrants harassing schoolgirls on the metro are widely discussed, and are driving a surge in support for new right-wing parties. There is also a sense of unease towards Chinese expats: While not particularly linked to crime, some Japanese doubt that they will uphold the desired standards of courtesy and etiquette.

There is no sense in Japan of multiculturalism being necessary, or the natural order of things, as there is in the modern West. For many Japanese, the solution to foreign residents being obnoxious on the metro, say, is to simply not have foreign residents.

But simply being a monoculture doesn’t account for the whole difference. The West has never been anything like Japan, for both better and worse. Our culture of individualism, which in many ways is a superpower, also causes us all to act in ways that Japanese would consider antisocial – and that prevent the creation of a metropolis like Tokyo.

In the West, most middle-class city-dwellers feel entitled to reserve a large chunk of public space outside their house to store their car for a nominal fee. This selfish urge runs so deep that no government has ever been able to deny it, despite the enormous hidden subsidy it entails. Huge chunks of prime real estate are lost.

In Tokyo there is almost no street parking. The streets are narrower, allowing more density; but they feel wider because in terms of useable space, they are. Trunk roads aside, there’s also no need for a pavement: The whole width of the street is for everybody, not just the minority who own cars.

Drivers adapt to the market conditions. Because space is no longer subsidised, most people buy normal-sized cars instead of giant SUVs. There’s also a booming demand for kei cars – small models that fit anywhere and also benefit from a tax reduction. They’re not sold in any other market, in a sign of how rare Japan’s urban planning model is.

As a tourist, this emboldens you to wander freely through residential neighbourhoods, seeing locals going about their business and perhaps finding a backstreet izakaya on the way back to your hotel. It feels freeing, and the press of cars in any European city feels restrictive in comparison.

Commons sense

Underlying this urban planning decision is an understanding that space is more efficiently used publicly than privately, and that space in a city is at a premium. To build a functioning metropolis, therefore, as little space as possible must be given over to private use.

That philosophy underpins the capsule hotel, where each guest’s private space is equivalent to a few coffins; dozens can be housed in each room. Nonetheless, they are primarily aimed at business travellers. In Japan, sharing space isn’t low-status or a sign of being broke. It’s just common sense.

To Western eyes, this can lead to a mismatch in expectations. I stayed at a capsule hotel in Sendai. My personal quarters were tiny and I had no private shower, so in one sense it felt like being in a youth hostel. On the other hand, I had access to a luxurious shared bathhouse, a gym and a reading room more typical of a high-end Western hotel. Not to mention a natty set of pyjamas.

To affordably have nice things in cities, three conditions appear to be necessary. First, a cultural willingness to share space at all social status levels. Second, a common understanding of etiquette that governs how these spaces should be used. Third, a very low crime rate to allow people to let their guard down.

In Japan, these conditions are met. People living in cities can therefore have nice things – a house downtown, a bath on business trips, a walk in a well-kept park – far cheaper than we can in Europe.

European cities are moving in the opposite direction. The little space that we do share – parks, public transport – is falling into disrepair, social trust is falling and crime is on the rise. People are retreating into private spaces, and it’s hard to blame them.

We’ll never be Japan, and we shouldn’t want to be. But if we could somehow meet it halfway, I wouldn’t complain.

I've lived in Japan about half of my life. You get some things and miss some things. Not having a private shower (or bath) is because there isn't a strong showering culture, there's a strong BATH culture (often shared public bath). Go on a hike, and at the end, there's a bathhouse (onsen), usually with a nice restaurant, too. Japan is a tightly controlled state, but, as a foreigner, you are not a part of that social control (unless you, like some recent tourists, do something truly egregious, like the elder man who carved his name into a temple (he was arrested and deported). Japanese aren't buying big SUVs because so many are struggling financially, the economy has stagnated for years, and many talk about their frustrations about this, working so hard, and not being where they expected. I think there is a Japanese concept of suffering that the West does not buy in to anymore. There is a consideration for others that makes every day life pleasant. On the walk to my son's school, for example, there is a 2 way road between a few sharp corners, and when cars pass each other, one has to pull up and wait or pull up on the curb and inch past the other one. This happens fairly often, with parents on bikes also passing, and kids as young as 6 walking themselves to school. I can't even imagine such as a scenario in NYC (where I'm from), it would be an accident every time.

It's a good reminder that, as Europeans, we shouldn't only look at American cities and pat ourselves on the back for the 'liveability' of our cities, but also at other examples like Japan that do many things better than us. Then again, we should also make a distinctions between larger cities (Brussels, Antwerp, Paris) and mid-sized cities (Ghent, Bologna) - the latter often striking a better balance.